Origins in the Late 19th Century: Portman’s Eastern Vision

The story of the August Order of Light begins with the figure of Maurice Vidal Portman, a young British colonial officer whose esoteric interests took root during his service in India. Portman arrived in India in 1876 as part of the Viceroy’s entourage, and instead of confining himself to colonial duties, he immersed himself in the study of local religions and occult traditions. By the early 1880s, Portman had reportedly “gone over to the native faith” – in other words, he became a devotee of Hindu and Buddhist practices – and was initiated into “almost all of the Occult Societies of India,” as noted by contemporary occultist John Yarker. Portman’s aim was ambitious: to bridge East and West in a new mystical rite. He envisioned an initiatory order that could transplant Eastern wisdom into a Western fraternal framework, drawing on systems like the Indian Sat B’hai (meaning “Seven Brothers or Seven Feathers”) which had captivated him.

In November 1881, while stationed in the remote Andaman Islands, Portman formally launched the Order that would later be known as the August Order of Light. The founding document dated 11 November 1881 laid out the Order’s rules, regulations, and rituals, bearing Portman’s signature as “Grand Hierophant Presiding in the West”. He initially called it the Mysteries of Perfection of Sikha (Apex) and of the Ekata (Unity), reflecting a blend of Eastern terminology (Sikha meaning Apex, Ekata meaning Unity) with an almost Masonic degree system. Indeed, Portman’s fledgling Order had a complex nine-degree structure divided into three sections, a numerological symmetry likely inspired by the Sat B’hai’s nine grades. The rituals he drafted were suffused with Eastern imagery: candidates progressed through grades with Sanskrit titles (e.g. Dikshita, meaning initiate), meditated on concepts like chakras and the subtle body, and even encountered Hindu and Buddhist deities in the ceremonial symbolism. This was quite unlike the Judeo-Christian and alchemical motifs familiar in Western occult orders of the time.

One notably progressive idea in Portman’s original plan was the inclusion of women – virtually unheard of in 19th-century fraternal orders. He outlined a side-degree called “Parvati” for female aspirants, led by an Abbess, wherein women could meet separately and even assist in “magical experiments”. However, he stopped short of full equality: women were “not to witness our signs or words” and held no direct authority over male initiates. The notion that female members could be “inspected” by the male Order was enigmatic (and, as one observer later quipped, there is no record of any such inspections actually occurring). Still, Portman’s willingness to involve women at all was a radical departure for his era, hinting at the inclusive, exploratory spirit that characterized his vision.

Despite these grand plans, Portman’s Oriental Order of Light (as it was often called in its earliest years) remained a private and somewhat nebulous project throughout the 1880s. Portman himself spent most of that decade in the Andamans, far from the metropolitan centres of occult activity in Britain. He initiated a few acquaintances into the Order’s first degrees – including notable occultists like Rev. William A. Ayton and Robert Palmer-Thomas – in England during home leave. According to later recollections, Portman even claimed a fantastical origin story for his own initiation: he said he had been “initiated in a bath of Mercury” during his travels, a statement that became part of the Order’s lore. (Bro B D Tinkler’s 1922 account humorously explains that the mundane reality behind this claim was that Portman suffered a head wound in a violent encounter with locals, and the “bath of Mercury” was a metaphor for a medical treatment that never came in time.) Such colourful anecdotes aside, the Order’s actual activity under Portman’s sole leadership was limited. He corresponded with fellow occult enthusiasts like Yarker and likely performed some informal rituals, but no large-scale lodge was established in this period. By the late 1880s, Portman’s enthusiasm for mainstream Freemasonry had waned – he wrote of being “disappointed in Masonry” – and he turned increasingly to esoteric pursuits for fulfillment.

Eastern Influences and the Sat B’hai

A key influence on Portman’s creation was the Sat B’hai, an obscure Indian mystical order. Portman had encountered it and even sought to revise its rituals with the help of native adepts. He saw the Sat B’hai as a kind of spiritual sibling to what he wanted to create in the West. Indeed, many structural elements of the August Order of Light were modelled on the Sat B’hai’s system.

Letters from John Yarker in 1890 reveal that some of the Order of Light’s early ritual material was actually drafted by a “Cabalistic Jew in London” and then amalgamated with the Sat B’hai rite. Yarker, acting with Portman’s permission, folded portions of Portman’s rite into a Sat B’hai “Perfection” degree, effectively blending the two. Modern scholars (such as Yasha Beresiner) conclude that Portman “merely [adopted] the principles and ‘shape’ of the already existing Sat B’hai ritual, flavouring it with Hindu and other oriental mysticism.” In other words, the August Order of Light was not an imported “ancient secret order” as romantic myths later suggested, but a synthesis; Portman’s personal fusion of Eastern concepts with Western fraternal structure.

By 1882, we get a fleeting glimpse of Portman’s progress. Yarker introduced Portman in a memo as someone who had “undertaken to get the Sat B’hai ritual revised by native Initiates & Adepts” and sought even the Dalai Lama’s blessing as an “Unseen Sponsor” for the project. Portman clearly aimed high. Yet for all this activity behind the scenes, little of the Order of Light was publicly visible. One might imagine Portman in the evenings at Port Blair (capital of the Andamans), by oil lamp, penning mystical regulations and letters to fellow occultists in England, keeping the spark alive on paper while the Order had no physical lodge.

Early Attempts and Decline of the First Order

Back in England, during Portman’s occasional returns, there were attempts to get the Order off the ground. In the early 1880s, Portman conducted initiations in London, hiring a house in Kilburn as a venue where he and his associates could perform the rituals. Among those early initiates were respected occult Mason Rev. W. A. Ayton and a certain Robert Palmer-Thomas. Palmer-Thomas took on the task of writing up some of the rituals, suggesting that Portman collaborated with others in fleshing out the degree ceremonies. Notably, both men and women were involved in these embryonic rites. Portman even employed a female medium or clairvoyant – referred to as a “lucid” – named Mrs. Linton Ellis (stage name Estelle), an actress and poet who assisted in the Order’s workings. This co-ed aspect made the Order of Light stand out amid the Victorian occult scene, where most organizations (the Golden Dawn being a prominent exception) were male-only.

However, these early gatherings faced unexpected headwinds. According to a later account, the members developed a paranoid conviction that their nascent Order was being “insidiously assailed by the Jesuits.” In one telling, this paranoia led them to disband the group entirely in fear. The reality, it appears, was slightly less dramatic but equally corrosive. Mrs. Ellis, the very medium they had employed, decided to convert to Catholicism. Her departure, and the prospect that she might reveal the Order’s secrets in confession, sent the remaining members into a panic. In a climate of such distrust, the tiny Order of Light essentially imploded. The brethren chose “the refuge of self-effacement,” dissolving the group to avoid any risk of exposure. Thus, by the mid-1880s, Portman’s first iteration of the Order of Light had gone dormant, “whether it went to sleep utterly for a season, I am not prepared to say,” writes Tinkler, “but after a considerable space it came into the hands of certain Masonic Brethren in Bradford.”

This period of dormancy lasted the better part of the late 1880s and 1890s. Portman himself grew disillusioned or simply preoccupied, and he eventually retired from colonial service in 1890, returning to England. By then, he seems to have recognised that he alone could not propel the Order of Light to sustainable life. The Order’s revival would need new energy and new leadership.

Revival in Bradford (1902): Pattinson, Edwards, and Westcott

If the August Order of Light’s “Eastern dawn” was in Portman’s India, its rebirth in the West took place in the unassuming industrial city of Bradford, Yorkshire. This unlikely venue was not chosen at random, as Bradford happened to harbour a circle of avid occultists around the turn of the century. Chief among them were Thomas Henry Pattinson and Dr. Bogdan E. J. Edwards. Pattinson was a prominent local Freemason and an enthusiast of esoteric Masonry, while Dr. Edwards was a learned mystic (and a medical doctor by profession). Both men were members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn’s Bradford lodge (Horus Temple No. 5) founded by Dr. William Wynn Westcott in 1888. Westcott, a renowned co-founder of the Golden Dawn and Supreme Magus of the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia (SRIA), played a pivotal role in this story. He had met Portman in the 1880s and shared his interest in Eastern mysticism. Westcott was instrumental in nudging Portman toward Bradford. In 1889, he arranged for Portman to lecture to a local Theosophical Society group there, hoping to spark interest in the Oriental Order of Light. Portman gave the lecture and even attempted to establish the Order in Bradford at that time, but the effort “was without success.” The late-Victorian Bradford brethren, it seems, were not quite ready for Portman’s exotic blend of Brahmin and Buddhist lore.

By 1900, however, the situation had changed. Portman, now back in England and in his early 40s, decided to pass the torch. Pattinson and Edwards were approached and he effectively handed over the dormant Order of Light to them, encouraging them to “make whatever alterations they thought necessary to attract Yorkshire Freemasons.” It was a calculated decision, given that Pattinson and Edwards both possessed the occult knowledge and the organisational skills to rebuild the Order on British soil. They also had Westcott nearby to advise. As one historical reflection notes, “I detect the hand of Dr. Wynn Westcott in the rituals we now work.” Indeed, Westcott almost certainly helped Pattinson and Edwards rewrite and modernise the rituals, blending his own Kabbalistic and Hermetic expertise with Portman’s Eastern framework. There is even some evidence that Madame H P Blavatsky might have had some input. However, primary credit for the revived system “must be given to Messrs. Pattinson and Edwards.” The two Yorkshiremen poured energy into adapting Portman’s once nebulous “Oriental Order” into a practical, well-structured society suitable for Western initiates.

Their work bore fruit quickly. By late 1901 or early 1902, Pattinson and Edwards had quietly begun initiating a few select brethren in Bradford under the Order’s banner. In the Masonic Hall at Halifax, there is a warrant signed by Portman himself, authorising Pattinson and Edwards to revive the Order of Light. In that brief document, Portman styles himself “Founder of the Order of Light” and gives his blessing in formal terms: “I… authorise T. H. Pattinson and J. B. Edwards to admit members to the Order and to hold meetings thereof and I confirm their past actions in so doing.” Although undated, this warrant was likely issued in 1901, implying that Pattinson and Edwards were already holding meetings and recruiting members before the official relaunch. Portman’s warrant was the green light that legitimised their efforts. Shortly thereafter, in January 1902, the August Order of Light was formally re-founded in Bradford.

Under the new charter, Pattinson and Edwards assumed the title of Arch-Presidents, establishing a dual leadership that mirrored certain occult fraternities (and perhaps harked back to the Sat B’hai’s two Presidents). They were also the first and second Guardians of Light, similar to the Master of a Masonic Craft lodge. This dual structure ensured continuity of leadership and was a clever way to distribute authority – a stark contrast to Portman’s solitary rule in the 1880s.

In these early days in Bradford, the relationship between the Order of Light and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn was very direct. Pattinson, Edwards, and Westcott formed a sort of triumvirate behind the scenes. Westcott had by that point withdrawn from the leadership of the Golden Dawn (he ostensibly resigned in 1897 under pressure from his employers), but remained an active mentor in fringe Masonry. He joined the August Order of Light, with records showing that Westcott attended nearly every Equinox meeting of the Order for twenty years and served as President of the Order’s governing body (Companions of Agni) in 1905.

In a 1917 lecture to the brethren, Westcott candidly explained his role: he had “joined the Order as one who would illustrate the Kabbalistic view of Divinity, the World and Man,” contributing “Christian, Hebrew and Mediaeval Western notions” alongside the Order’s Eastern content. In essence, Westcott infused Golden Dawn-style Hermeticism into the Order of Light’s curriculum, tempering the Eastern and Egyptian knowledge of Pattinson and Edwards with Western esoteric philosophy. This cross-pollination led to a richly syncretic system. Ritual elements and symbolism were freely reused and adapted; for example, many diagrams, tools, and teachings from the Golden Dawn’s Horus Temple in Bradford found a second life in the Order of Light. Fred Scott later noted that when the Golden Dawn temple in Bradford disbanded in 1907, the August Order of Light “inherited various artefacts from that Lodge.” These included diagrams, temple furnishings and likely texts that would be preserved for decades in the Order’s archives. The overlap in membership also helped continuity as twelve of the fifteen founding members had also been members of the Horus Temple, bringing with them a familiarity with ceremonial magic and mystical symbolism. In sum, the August Order of Light and the Golden Dawn shared an egregore, shared founders (Westcott in particular), and shared some content, yet diverged in emphasis – the former looked East, the latter West.

The First Temple in Bradford: Salem Street and King’s Arcade

The revived Order’s first meetings in 1902 were discreet and somewhat secretive. The minutes reveal that the initial gatherings took place in the Masonic Rooms on Salem Street, Bradford, which Pattinson and Edwards had access to. However, the brethren soon sought a space of their own. They found it in a modest location in a disused basement of a pub on King Street in central Bradford.

By June 1903, the Order had secured an attic at 81 King’s Arcade (off Market Street) and began converting it into a dedicated temple. By September 1903, the new temple was ready, and the Order of Light had a permanent home that would serve it for the next 36 years.

Contemporary accounts and later recollections paint a vivid picture. The space was lit by flickering oil lamps and candles, as it was decades before electric light would be feasible for them. The members – respectable Edwardian gentlemen in daily life- donned colourful robes and adopted Sanskrit ritual titles during ceremonies. The scent of sandalwood and frankincense perfumed the air, accompanying “strange words of Hindi and Pali” woven into the opening odes. To transform the dingy space into a temple of the East, art played a crucial role. The daughter of one of the founding members, a young woman who had grown up in India, volunteered her talents to decorate the walls and columns. She produced “superb murals” in authentic hues that, it was said, “most Western artists find impossible to produce.” On the supporting pillars, she painted exotic figures – symbolising the union of East and West in the Order’s philosophy. The overall effect was immersive.

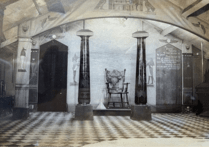

Interior of the first Bradford Temple (King’s Arcade attic, c.1904), showing the eclectic Eastern décor. Multiple painted pillars depicted gods and symbols from various traditions, and the vaulted arches were adorned with Indian and Egyptian motifs. A large mural of a setting sun dominated the western wall. The pillars came from the Golden Dawn Horus Temple. These black and white photographs of the Kings Arcade Temple were taken prior to removal in 1939 by Brother JM Martin, Guardian of Light 1945-46.

One member recalled that the temple was arrayed with multiple pillars painted with gods and goddesses from different pantheons. Facing East, one saw Hindu deities; facing West, Egyptian gods; on the North wall were Greek figures, and on the South, Roman ones. The four directions thus corresponded to four great civilisations’ mythologies – a symbolic “gathering of all lights” in one place. Overhead, arches were decorated with further Indian and Egyptian motifs, and along the West wall glowed the image of the setting sun, a potent emblem perhaps of the Light’s journey from East (where the sun rises) to West (where it sets). Brothers of the Order later took pride in noting that such Oriental flourishes made their temple distinct from any other Masonic body’s lodge: this was truly an “Order Beyond the Craft” that stood out “both from the point of view of the ritual as well as its composition”.

The impact of this richly decorated environment on candidates was profound. Many years later, an initiate described his first entrance around 1905 into the King’s Arcade temple: “the Eastern atmosphere – and I was ‘sold’ on the Order of Light.” The ambience alone convinced him he had found a spiritual home. The Order’s blend of familiar fraternal structure with exotic symbolism had a magnetic appeal to those open-minded seekers who had served in the Empire or studied Theosophy. It was the height of the British Raj, and many prospective members were retired colonial officers or scholars who “hankered after Masonry with a flavour of the East.” The timing was perfect: Western esotericists were looking eastward (the Theosophical Society was flourishing, translations of Eastern scriptures were popular, etc.), and here was a Masonic-styled Order that promised exactly that synthesis.

Growth and Golden Years (1904–1939)

Throughout the first two decades of the 20th century, the August Order of Light in Bradford grew steadily, if quietly, in both membership and repute. By design, the Order kept a low profile (no public recruitment, members were selected carefully), but word spread in occult and Masonic circles about this unique brotherhood. By the early 1920s, they had attracted a number of notable members, including local dignitaries.

In 1924, upon the death of Dr. Edwards (who had served as Arch-President for over two decades), the Order privately printed an In Memoriam book that gives a snapshot of its reach. The subscriber list in that 1924 memorial volume included 43 names – not only local Yorkshiremen, but also members as far afield as Constantinople, Sydney, Cleveland, and Durban. The Light lit in Bradford had already cast its rays internationally via the Empire’s networks. (Notably, Dr. Westcott himself emigrated to South Africa around 1918 and continued Order of Light work there until his passing in 1925.) One especially intriguing name on the 1924 subscriber list is Bro. Rudyard Kipling. Although never a member, the famous author was a Freemason with deep knowledge of Indian culture, and it appears he lent his support or interest to the Order of Light. Such patronage, even if informal, underscores how well-regarded the Order had become in certain circles.

It was around this time (the 1920s) that the organisation solidified its identity as “The August Order of Light.” Earlier, the Order had sometimes been referred to by members as the “Oriental Order of Light” (echoing Portman’s terminology). But by 1924 the official usage settled on August Order of Light, with “August” meaning venerable or noble. Tellingly, the 1924 memorial book’s epilogue describes it as “this August and Oriental Order of Light,” acknowledging that it was both august (exalted) and oriental (in inspiration). In practice, veterans still called it the Oriental Order in conversation, but formally, the shorter name prevailed.

Through the 1910s and 1920s, the Order thrived in a genteel way. Meetings were held at regular intervals (often on the Equinoxes and Solstices, in line with its mystical character). The content of meetings went beyond rituals; there were lectures on occult subjects and study circles where members examined texts on Theosophy, Kabbalah, Buddhism, etc. For example, in the early years at King’s Arcade, the brethren organised a series of study evenings in which they dissected Esoteric Buddhism (an 1883 Theosophical work by A. P. Sinnett), with different brethren leading discussions and even using an image of Osiris as a “talking stick” to regulate debate. This intellectual side of the Order kept members engaged between degree ceremonies, and cemented the Order’s reputation as a serious, contemplative society rather than a mere degree mill.

Westcott’s influence in these years was significant – he attended almost every major ceremony until about 1918 and gave frequent addresses. In 1905 he even became the President of the Companions of Agni, the governing body within the Order that supervised members’ studies. In a special Q&A lecture in 1917 (his hand-amended version of that lecture is the first chapter in this book), Westcott answered members’ questions about how the Order of Light related to Theosophy and the Golden Dawn, making it clear that while he contributed Western esoteric knowledge, he acknowledged the Order’s primary Eastern focus. The balance of East and West was carefully maintained.

By the 1930s, the Order had outgrown its temple. More precisely, the building housing King’s Arcade was due for redevelopment. In 1939, just before the onset of World War II, the Order moved to new premises at 52a Godwin Street in Bradford. This move proved to be fortunate and timely. Godwin Street was (and still is) a main thoroughfare in Bradford. Coincidentally, it had been renamed in honour of Sir J. Arthur Godwin – a prominent member of the Order of Light who served as Bradford’s first Lord Mayor. The new premises consisted of the top two floors of a warehouse building above a tobacconist’s shop. Here, the Order could design a larger, purpose-built temple and, importantly, install modern electric lighting. At last, the Order of Light could truly live up to its name by illuminating its rituals with electric light – a practical improvement that required a space they could modify freely, by running wiring and fixtures.

Under the direction of Arch-President Henry Williamson, a mill owner who volunteered his company’s idle tradesmen, the members outfitted the new Godwin Street temple “as though it were required to last a thousand years.” Carpentry, painting, and electrical work proceeded, even as war loomed in 1939. The result was an impressive sanctum that opened in spring 1940. Much of the décor from King’s Arcade was carefully transferred to Godwin Street – they literally removed murals and fixtures where possible to reuse in the new temple. According to Fred Scott, those decorations were originally from the Golden Dawn’s Horus Temple and had been preserved through the years. In the Godwin Street attic, they were given new life, integrated with fresh additions. Thus, the continuity of the Order’s symbolic art was maintained.

One of the paintings from the arches created for the King’s Street Temple, showing Aruna, the charioteer of Surya, the Sun. This piece is awaiting restoration in storage in Halifax.

Entering the Godwin Street temple for the first time in the 1940s must have been an awe-inspiring experience. An account by Bro Andrew Stephenson (who joined later but heard descriptions from elder members) describes a secretive entrance accessed via a back alley, through a tunnel, and up several flights of stairs from gloom into gradually increasing light and splendour – an almost allegorical ascent from darkness to light. On the top floor, behind a narrow door, was a lofty chamber filled with the scents and sights of the East: wall hangings, painted scenes of dawn and dusk, altars draped in embroidered cloth, and the warm glow of lamps reflecting off gilded symbols. As one new initiate was told when he marvelled that such an “unlikely city as Bradford” was chosen for this Eastern sanctuary: “the stars said so.” The founding of the Order, he was led to believe, had an astrological destiny, a touch of mystique that reflected the Order’s love for symbolism and myth.

Trials of War and Decline (1940s–1960s)

Every esoteric order faces challenges over time, and the mid-20th century tested the August Order of Light in numerous ways. World War II naturally disrupted the regular activities of many fraternal groups. Several members were called to military service; others had duties on the home front. The Order of Light did manage to continue its ceremonies during the war (with older members or those in reserved occupations keeping it going), but there was a noticeable slowdown in new admissions. By the end of the war, the demographics of the Order had skewed older.

The post-war social changes also affected membership. The 1950s and 1960s saw a general decline in interest in the old Victorian-style occult fraternities; younger generations were less inclined to join formal lodges, instead turning to new spiritual movements or simply not engaging at all. In Bradford, the core members of the Order of Light grew old together. By the 1960s, meetings had an air of a “cosy club” – a tight-knit circle of elderly gentlemen meeting more out of loyalty and habit than active spiritual quest. As one later observer noted, the Order was drifting, its once vibrant flame slowly dimming with each passing of an old guard member. Few new recruits were coming in, and those who did often left discouraged by the lack of energy.

A severe blow came from outside: in the late 1960s, the owners of the Godwin Street building (the tobacconist’s business) announced plans to close and possibly sell the property. In 1969, the Order of Light received notice it might have to vacate its temple within six months. This news struck the remaining members hard. They had invested so much in that temple both materially and emotionally that the prospect of losing it led some to believe that perhaps the Order should simply close down if forced out. At a special meeting in October 1969, despairing voices even suggested surrendering the Order’s independence by merging into another Masonic body. They approached the Allied Masonic Degrees (AMD) about the possibility of subsuming the Order of Light as one of the AMD’s side-degrees. It was a last-resort idea born out of panic: effectively handing over the Order’s heritage in exchange for a dignified retirement.

Fate intervened in the form of an enlightened ally. The Grand Master of AMD at that time, Arthur Murphy, was himself a member of the Order of Light. Upon seeing the proposal, Murphy realised that such a merger would sound the “death-knell” for the August Order of Light as its complex Eastern rites would weaken under the umbrella of an unrelated organisation. Murphy vetoed the merger, telling his brethren in Bradford to “think again” and urging them to find an alternative solution. Chastened and motivated by this, the remaining Yorkshire members rallied. If Bradford could no longer host the Order, perhaps the Light could be carried elsewhere without being extinguished.

Survival and Adaptation: The Move to London and Beyond

Among the few younger members in the late 1960s were Fred F. Scott (by then serving as Secretary of the Order’s Council of Elders) and John Edward Nowell Walker. Walker in particular had a bold idea: “If you close down the Order, I will open it in London.” This was a shocking proposition to the staunch Yorkshiremen. London was historically viewed with suspicion as a potential usurper of northern Masonic traditions. But Walker’s determination, backed by Fred Scott and another energetic member, Louis C. Clark, helped turn the tide. Rather than let the Order die or be taken over, they decided to expand by establishing a new Temple No. 2 in London, while maintaining Temple No. 1 (if possible) in the North.

Walker teamed up with a London-based occultist, Bro Andrew Stephenson, who had recently joined the Order and was passionate about its survival. In the early 1970s, they scouted locations in London. Renting a full lodge room in the city was far beyond their means. Andrew Stephenson offered the attic of his own home in the London suburb of Blackheath as the new temple space. It was not central London (though near a railway station), and it was modest in size, but in a stroke of serendipity, they discovered that by moving one wall a few feet, the attic’s floor plan would match the proportions of the Bradford temple’s layout almost exactly. This coincidence felt like destiny; they took it as a sign that the plan was meant to be.

Convincing the Bradford elders to approve this plan required some diplomacy. Memories of regional rivalries (Yorkshire vs. London) ran deep. To reassure everyone, the London team pledged total loyalty to the Northern leadership. Andrew Stephenson even recalls a heated exchange in which he proved his “Northern-ness” (he was brought up in Nottingham) to a sceptical Yorkshire brother, which Arch-President John Leach overheard, easing Leach’s worries that the Order might be hijacked by “Southerners”. With trust established, Arch-President Leach approved the founding of a London Temple on the condition that Bradford remained the Order’s guiding centre and that the London group operated under Bradford’s authority.

Thus empowered, a handful of members from both North and South spent several years in the 1970s converting Stephenson’s attic into a fully equipped Temple of Light. The story of this construction is a charming chapter in the Order’s annals, showcasing the ingenuity and devotion of the brethren. They built nearly everything from scratch or scrounged materials. For pillars, they collected discarded plywood circles from a factory to stack into column drums, reinforcing them with scrap wood and even weighting them with old cast-iron sewer covers for stability. The spherical globes atop the pillars? Those were repurposed toilet cistern floats, painted to look like celestial orbs! The pillars were then covered in bookbinders’ cloth and paint, emerging as stately as any professional lodge furniture. Walls were lined with canvas on which a friendly artist recreated the mural panels from Bradford (using colour photographs of the original temple as reference) so that the London temple would have the same atmosphere. Even the large “setting sun” scene that adorned the west of the old temple was replicated by a local sign-painter (minus some fanciful embellishments he wanted to add).

Members of Temple #2 in the 1970s at Blackheath

The northern members contributed whatever they could. During the demolition of Godwin Street in 1970, Fred Scott travelled to Bradford with a van and, with Louis Clark, salvaged as much as possible: chairs, lamps, ritual ornaments, even the lodge crockery and cutlery used for festive boards. These were hauled down to London and stored in Stephenson’s house until the attic was ready – providing great motivation to finish the project lest his home remain a warehouse of esoterica! By late 1977, Temple No. 2 in London was completed. In a special consecration ceremony, the Arch-Presidents from Yorkshire came down to formally dedicate the new temple. They conducted a beautiful ritual (drafted by John N. Walker for the occasion) to ignite the Light in its new home, complete with prayers, blessings and of course a toast of champagne.

With that, the Order of Light became bi-regional. The London temple started with a small membership, so in its first year, they only worked the First Degree repeatedly until enough new initiates had joined to fill officer roles for higher degrees. The Bradford elders mentored their Southern brethren closely. In the second year, Louis Clark and Fred Scott travelled down to help the Londoners conduct a Passing Degree ceremony properly (even gifting them a needed ritual implement, the “Cone”). By the third year, the London temple was able to function independently, with occasional visits from Northern members for important meetings.

Meanwhile, the original Temple No. 1 moved from Bradford to York in the early 1970s. Unable to stay in Godwin Street or find affordable space in Bradford, the Order took up rooms at Castlegate House in York, about 30 miles away. John Leach and the Council of Arch-Presidents ran the Order’s

administration from there for some years, summoning London officers to York for joint meetings on occasion. Eventually, by the 1990s, the northern base would shift again to Halifax (closer to Bradford), where it remains today as the headquarters of the Order. Throughout all this, the partnership between North and South held steady. The Arch-Presidents kept a watchful eye to ensure the London temple maintained the same standards and rituals – a fact humorously illustrated when Will Vernon (Arch-President in the late 1970s) cautioned the creative John Walker “to make no ‘innovations’ in the ceremonies” now that London was up and running. The guardians of tradition were gentle but firm: the sanctity and uniformity of the rite had to be preserved across both temples.

One important institutional innovation that emerged in this era was a strict vetting process for new candidates. Having nearly lost the Order once, the leaders became keenly aware of the need to attract serious, dedicated members, not mere “gong collectors”. Thus, from the 1970s onward, the Order instituted the rule that any prospective member must first present an original research paper on an occult topic (non-Masonic) to the Order, which the brethren would evaluate before approving the candidate. If the paper (and the man) showed genuine insight and earnestness, only then would initiation proceed. This practice proved highly effective in screening out frivolous applications. Many who inquired quietly dropped away upon learning they had to produce real work; those who remained and fulfilled the requirement tended to be genuinely passionate souls who became assets to the Order.

This tradition of “scholarship before membership” remains in place to this day. The Book of Tau (rules and regulations of the Order) states that “All new members are required to write a piece of work on an occult, non-Masonic topic of their choosing before initiation and then on taking each of the subsequent degrees”. Quality over quantity became the Order’s byword, potentially one of the key reasons it survived when many other groups expanded rapidly and collapsed. The reader can judge this for themselves whilst reading the various contributions to the present volume.

By the 1980s, the August Order of Light had not only survived its near-death experience but was quietly thriving again, though on a smaller scale. In the early 1990s, a long-standing member wrote that this “quasi-Masonic Order” had proven to be “a story of success.” It had “brought much pleasure as well as an insight into the ways of Eastern peoples without the culture shock,” effectively fulfilling Portman’s century-old dream of a Western gateway to Eastern wisdom. The Order’s ongoing vitality, he noted, depended on upholding two principles: active contributions from members and careful selection of initiates. As long as each new brother contributed his “two-penn’orth” (two cents) of effort and knowledge to the collective, the Egregore or spiritual “group soul” of the Order would stay strong. And as long as they admitted only those truly suited, the family-like atmosphere and sincere purpose would be maintained. That said, the August Order of Light is not an invitational order, and any mason may apply for membership.

Legacy and Continuity: The Scott Collection and the Modern Order

One tangible link connecting the Order’s present to its past is the Scott Collection – a remarkable archive of artefacts and documents that spans the Order’s entire history. Named after Fred Scott, who played a key role in preserving it, the Scott Collection has been quietly maintained by the August Order of Light for over a century.

It almost miraculously mirrors the Rosicrucian legend of Christian Rosenkreutz’s tomb that opened after 120 years: after about 120 years of obscurity, the Order’s treasures were revealed for study and celebration. The collection holds a wealth of esoteric heritage. Amongst the items are original Golden Dawn ceremonial diagrams, handwritten ritual manuscripts from the 1880s, the Order’s original warrant from Portman, early membership rolls, beautifully carved wands and lamens (breastplate emblems), banners, and extensive correspondence shedding light on the occult scene in West Yorkshire before the First World War. In short, it is a complete time capsule of the Order’s and Bradford’s occult history. (Interestingly, what the collection does not include are things like minute books or certain swords and papers one might expect – indicating some items were lost or perhaps remain hidden elsewhere.)

The journey of the Scott Collection is itself part of the Order’s story: when the Godwin Street temple closed in 1970, Fred Scott moved the archives and items into Louis Clark’s workshop for safekeeping. In 1973 Clark became Arch-President, and in 1977, upon John Leach’s passing, he appointed Fred Scott as co-Arch-President. When the Order relocated to Halifax in 1991, Fred formally handed over the entire trove to two rising members, Michael Bottomley and Philip Standfast, who would later become (and remain) the Order’s Arch-Presidents in the 2000s. After Fred’s own passing (in 2008), it was decided to name the collection in his honour. It was a fitting tribute to the man who, perhaps more than anyone of his generation, ensured that the Light in Extension (to borrow a Golden Dawn phrase) would not be extinguished.

As of 2025, the August Order of Light remains a modest yet truly international fraternity. From its single lodge in Bradford, it gradually spread as members relocated worldwide. Today, there are active Garudas (temples), not only in England (Yorkshire and London) but also Australia, India, various European nations, parts of Africa, and North America. The Order’s worldwide presence is confined to those who actively seek it. It does not advertise, so someone living in those countries might never learn about it unless they are part of Masonic or esoteric circles. Yet it is precisely this low profile and focus on quality that keeps it healthy.

The internal structure has shifted slightly. Governance of the whole Order under two Arch Presidents, whose authority is absolute. They are assisted by the Council of Agni (named after the Vedic fire deity, symbolising the supreme guiding flame). Each local temple is led by a President (5-year tenure) and a Guardian of Light (one-year tenure), supported by a “Seven Companions of Garuda,” who form a lodge committee. The dual leadership model established by Pattinson and Edwards is still respected; two Arch-Presidents balance each other’s wisdom, and significant decisions still require their blessing, maintaining gentle central oversight. Perhaps this is why it remains the longest surviving occult body in the world?

Importantly, the spiritual ethos of the Order remains what it was in Portman’s and Westcott’s day: a syncretic quest that respects both Eastern and Western esoteric traditions. A modern historian might describe the August Order of Light and the Golden Dawn as sibling orders that inherited a shared 19th-century occult revival spirit but expressed it differently. The Golden Dawn, rooted in Western ceremonial magic, worked with Kabbalistic names and Enochian lore; the Order of Light incorporated yoga, chakras, karma, and Eastern deities alongside Masonic and Rosicrucian motifs. Many individuals have historically belonged to both orders (or their descendant groups), finding no conflict in pursuing multiple paths. The August Order of Light’s distinctive “flavour” is its particular blend. One might study the Bhagavad Gita and Buddhist sutras in one meeting, and astrological or alchemical texts in another, reflecting the broad scope originally championed by Pattinson and Edwards. Such diversity of study has only increased as the Order spread globally and welcomed people of many cultural backgrounds. As you will see from this compendium, a paper presentation at an Order meeting might explore Sufi mysticism or Taoist philosophy as readily as the Upanishads or Kabbalah. The overarching principle remains the same: through disciplined ritual and earnest scholarship, members seek to ignite the “inner light” of understanding within themselves and in fellowship with one another.

Intellectually, the Order functions almost like an esoteric academy. Its insistence on original research by each member at every stage has produced an archive of lectures and papers that document the evolving interests of its initiates. These papers, kept in the Order’s private library, create a rich tapestry of insight – a written egregore alongside the spiritual one. Every generation adds its chapter to the story, both through deeds and words.

In conclusion, the August Order of Light remains a testament to the power of syncretic vision and fraternal devotion. It began with the convergence of East and West in one man’s mind and continues as a harmonious chorus of many voices across continents, all united in the quest for Light. Its history – from the Andaman Islands to Yorkshire mills, from candle-lit cellars to electrified temples, from near oblivion to a quiet renaissance – reads almost like an allegory of spiritual alchemy: base elements transmuted into gold, darkness transfigured by light. Yet, it is very much a human story too, shaped by the dedication, foresight, and heart of individuals like Portman, Pattinson, Westcott, Edwards, Leach, Scott, and their successors. Light has always been extended from one era to the next, as long as there are seekers willing to carry it.

References:

- Melissa Seims, Light in Extension: The Magical Life of the Horus Temple and the August Order of Light (2025).

- Fred F. Scott, “History of the August Order of Light” (lecture delivered March 2002).

- Andrew Stephenson, “Reflection on the History of the Order” (1992).

- Douglas Bruce Tinkler, “Order of Light” (1922).

- Yasha Beresiner, The August Order of Light – Origins and History of a Little Known and Respected Order (c.2009).

Tim Brown,

Secretary General August Order of Light

Guys Hill, Australia, July 2025